"For an organism to be identified and then recognized as a new species, it must be completely understood.

"The battery of tests required to identify a particular species in a sample is extensive," says Pikuta. "These species are killed by the presence of oxygen, so great care must be taken to protect them." "Collecting samples from the muddy bottom of this lake and keeping them alive can be tricky business," says Hoover. Finding new species in this abundant collection of microbial life is a detective story worthy of Perry Mason or Hercule Poirot. They found it living with Tindallia californiensis and perhaps hundreds of other microbial species in Mono Lake mud samples. Tindallia californiensis (pictured at the top) thrives in highly alkaline conditions (pH 8-10.5) and at salt concentrations near 20%.Įarlier this year Hoover and Pikuta announced another strange microbe: Spirochaeta americana. (For comparison, a pH of seven is neutral 14 corresponds to pure lye.) Surprisingly, though, Mono Lake supports a wide array of life from microbes, to plankton, to small shrimp. It is almost three times saltier than sea water and has a pH of 10, about the same as WindexTM, a household glass cleaner. Mono Lake is an extremely salty and alkaline body of water. Image left: Elena Pikuta and Richard Hoover in their laboratory at the National Space Science and Technology Center. This month they've announced a new species of extreme-loving microorganism, Tindallia californiensis, found in California's Mono Lake. NASA scientists Richard Hoover and Elena Pikuta are among the hunters. Finding extreme life here on Earth tells us what kind of conditions might suit life "out there." Searching for life in the Universe is one of NASA's most important research activities. To find out how big, researchers are going deeper, climbing higher, and looking in the nooks and crannies of our own planet. The Goldilocks Zone is bigger than we thought. Whole ecosystems have been discovered around deep sea vents where sunlight never reaches and the emerging vent-water is hot enough to melt lead. Scientists found microbes in nuclear reactors, microbes that love acid, and microbes that swim in boiling-hot water. In the past 30 years, our knowledge of life in extreme environments has exploded. Image right: A false-color electron micrograph image of Tindallia californiensis. All life known in those days was confined to certain limits: no colder than Antarctica (penguins), no hotter than scalding water (desert lizards), no higher than the clouds (eagles), no lower than a few mines (deep mine microbes).

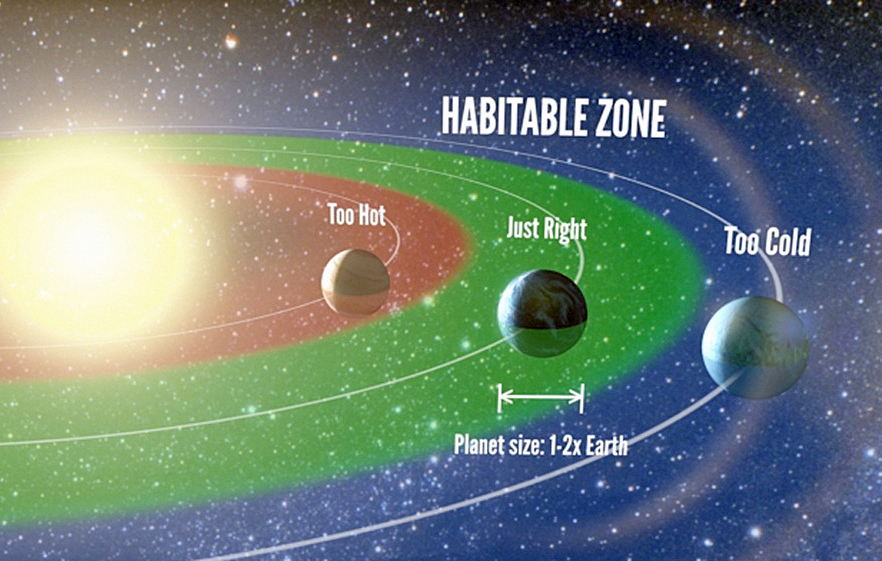

The Goldilocks Zone seemed a remarkably small region of space which didn't even include the whole Earth. Researchers of the 1970's scratched their heads and said we were in "the Goldilocks Zone." Somehow, though, we ended up in just the right place with just the right ingredients for life to flourish. A little farther away, the Earth might be like cold arid Mars. If Earth, however, were a little closer to the sun, our planet might be like hot choking Venus. Our planet has liquid water, a breathable atmosphere, a suitable amount of sunshine.

Only Earth was just right for life, they thought. Mars and the outer planets were too cold. Scientists hunting for alien life can relate to Goldilocks.įor many years they looked around the solar system.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)